The following text is by Rebecca Barrett-Fox, a guest speaker at Stahl Mennonite on Sunday, June 19, 2016.

Thank you for the kind introduction. And thank you all and especially to pastor Bob Brown for the invitation to be here. I’m especially grateful for the presence of guests at Stahl Mennonite today. It’s wonderful to be sharing space up here with Krista and Leah Rittenhouse, who are old friends from my days at Hesston College. Their presence is a real blessing to me. And I also want to recognize Father’s Day and to acknowledge that this day can be painful for some. For those for whom it is difficult to come to church on Father’s Day, thank you for being here.

The Parable of the Ten Virgins. I must confess to you that I have chosen, in response to the fact that you all are studying the parables this summer, one of my least favorite passages of scriptures. I neither like nor understand the parable of the virgins—which should have been good reasons for me not to select it for today’s passage. In fact, I really don’t like it, and I really don’t understand it—or maybe it is more fair to say that I fear I do understand it, and I don’t like what I understand.

To recap the story: A wedding is about to happen. Traditionally in first century Jewish culture, the bridegroom would come to the house of the bride’s family, where they would go through a marriage ceremony, then the couple would leave, sometime after dark, to parade through the streets on the way back to his home for days of celebration. Attendants would need to carry lamps or torches along the way to light the street. Those who participated in the marriage parade without a light might be assumed to be wedding crashers or, worse, thieves.

Ten women are waiting for the bridegroom to come. Five of them are ready, with their lamp in hand and oil in jars. Five, though, were not prepared. They were “foolish” in this story, because while they had their lamps, they did not have any oil.

The groom was taking his time coming, and the ten women fell asleep. When midnight rolls around and they hear the procession coming their way. They awake! It’s party time! They all get their lamps out, which is when the foolish virgins realize that they are without oil. They ask to borrow some from their wiser friends, who tell them no—each wise virgin has enough oil for herself but worries that she won’t have enough to share. Each wise virgin refuses to share, just in case. The unprepared virgins are told to go buy some more oil if they want it. The foolish virgins head to out to find someone to sell them oil at this late hour, and, while they are gone, the groom arrives. They miss it.

The wedding party who is present go into the banquet. And get this—they shut the door behind them. The five women who are looking for the oil they should have already had are locked out. When they finally get the oil and return, they knock on the door and ask to come in. The groom tells them, “I don’t open the door for strangers.” Ouch.

Thank you for the kind introduction. And thank you all and especially to pastor Bob Brown for the invitation to be here. I’m especially grateful for the presence of guests at Stahl Mennonite today. It’s wonderful to be sharing space up here with Krista and Leah Rittenhouse, who are old friends from my days at Hesston College. Their presence is a real blessing to me. And I also want to recognize Father’s Day and to acknowledge that this day can be painful for some. For those for whom it is difficult to come to church on Father’s Day, thank you for being here.

The Parable of the Ten Virgins. I must confess to you that I have chosen, in response to the fact that you all are studying the parables this summer, one of my least favorite passages of scriptures. I neither like nor understand the parable of the virgins—which should have been good reasons for me not to select it for today’s passage. In fact, I really don’t like it, and I really don’t understand it—or maybe it is more fair to say that I fear I do understand it, and I don’t like what I understand.

To recap the story: A wedding is about to happen. Traditionally in first century Jewish culture, the bridegroom would come to the house of the bride’s family, where they would go through a marriage ceremony, then the couple would leave, sometime after dark, to parade through the streets on the way back to his home for days of celebration. Attendants would need to carry lamps or torches along the way to light the street. Those who participated in the marriage parade without a light might be assumed to be wedding crashers or, worse, thieves.

Ten women are waiting for the bridegroom to come. Five of them are ready, with their lamp in hand and oil in jars. Five, though, were not prepared. They were “foolish” in this story, because while they had their lamps, they did not have any oil.

The groom was taking his time coming, and the ten women fell asleep. When midnight rolls around and they hear the procession coming their way. They awake! It’s party time! They all get their lamps out, which is when the foolish virgins realize that they are without oil. They ask to borrow some from their wiser friends, who tell them no—each wise virgin has enough oil for herself but worries that she won’t have enough to share. Each wise virgin refuses to share, just in case. The unprepared virgins are told to go buy some more oil if they want it. The foolish virgins head to out to find someone to sell them oil at this late hour, and, while they are gone, the groom arrives. They miss it.

The wedding party who is present go into the banquet. And get this—they shut the door behind them. The five women who are looking for the oil they should have already had are locked out. When they finally get the oil and return, they knock on the door and ask to come in. The groom tells them, “I don’t open the door for strangers.” Ouch.

Let me tell you a different story about two virgins. One of them spent a considerable number of hours of her teenage years stranded at the side of the road, having run out of gas, too distracted by the radio to notice the bright red indicator light on the dashboard telling her that she would, indeed, soon be flagging down a stranger for help. The second virgin was never so irresponsible. She probably still never lets her minivan fall below empty. The first virgin is wiser now and knows exactly how many miles she has left when that indicator light comes on, though she may also have pushed her luck sometimes and continued to drive even when the computer chip in her gas tank tells her that she has 0 miles left in the tank. The second sister--Did I say “sister”? Oops.—well, the second sister, she has never let the tank get to 0. The first sister arrives for a visit, a day late or a day early, or maybe two days late or two days early, with a passel of kids and a dog and a fish that she carried the whole way from Arkansas in a travel coffee mug and a bundle of dirty laundry and a lot of love but no plan at all. The second sister has a Google calendar that she sends in advance to make sure their schedules coordinate. Of course, they cannot, because the first sister has no schedule.

It’s true—that was a biographical sketch, and though many of you don’t know me well, you do know my sister Sarah, a lay leader at this church. Sarah kindly invited me here, and before I arrive in town, she sent me her Google calendar. I had heard of such things, but, like Good Housekeeping and Pinterest, had avoided Google calendar because that kind of thing makes me feel inadequate. In fact, when she sent it, I let it linger in my inbox. I couldn’t even open it for a few days because I was so intimidated by that level of organization. When I did open it, I immediately felt bad about myself, so I shut it and haven’t opened it since.

And you can now guess why I don’t like the parable of the virgins much. I tend to be the kind of virgin who is too busy doing something else to notice that I’m out of oil. In fact, even if you remind me that I’m out of oil, I might go to the oil store and get there and forget entirely what I came for and end up buying the tools for some other project that I may or may not begin and may or not may finish, plus some Swedish fish at checkout because I got distracted, plus I forgot to eat lunch. I’m sure that would not happen if I had a Google calendar, but there I am: out of oil. And just in time for the party to start!

And so, in this story, I’d be out there, finally with oil in hand but still missing the banquet.

It’s true—that was a biographical sketch, and though many of you don’t know me well, you do know my sister Sarah, a lay leader at this church. Sarah kindly invited me here, and before I arrive in town, she sent me her Google calendar. I had heard of such things, but, like Good Housekeeping and Pinterest, had avoided Google calendar because that kind of thing makes me feel inadequate. In fact, when she sent it, I let it linger in my inbox. I couldn’t even open it for a few days because I was so intimidated by that level of organization. When I did open it, I immediately felt bad about myself, so I shut it and haven’t opened it since.

And you can now guess why I don’t like the parable of the virgins much. I tend to be the kind of virgin who is too busy doing something else to notice that I’m out of oil. In fact, even if you remind me that I’m out of oil, I might go to the oil store and get there and forget entirely what I came for and end up buying the tools for some other project that I may or may not begin and may or not may finish, plus some Swedish fish at checkout because I got distracted, plus I forgot to eat lunch. I’m sure that would not happen if I had a Google calendar, but there I am: out of oil. And just in time for the party to start!

And so, in this story, I’d be out there, finally with oil in hand but still missing the banquet.

[Photo courtesy of Ailecia Ruscin; all rights reserved.]

[Photo courtesy of Ailecia Ruscin; all rights reserved.] Let me switch topics.

I have spent a number of years now studying Westboro Baptist Church. It’s a small—larger than Stahl Mennonite, but not by much—congregation from Topeka, Kansas. It’s an independent Baptist church, not associated with any denomination, though they call themselves Primitive Baptists, theologically speaking, though other Primitive Baptists say that they aren’t. How many folks here have heard of them? And has anyone seen them in person?

Well, this church is most famous for its picketing at funerals. Since the early 1990s, they have shown up at funerals, as well as many, many other events, including high school graduations, concerts, public lectures, and other events, to preach their message. For the first 15 years or so, that message focused on their claim that God hates people who are not heterosexual. In the mid-2000s, as American casualties from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan started climbing, they turned their attention to God’s hatred of all of America, as evidenced by soldiers killed in combat. It was that claim that landed them before the Supreme Court in 2010. They picketed the funeral of a Marine from York, Pennsylvania, and though they did not break the law in doing so, the father of the fallen Marine sued them. He won, then he lost the appeal, and he lost before the Supreme Court. So they continue to picket.

This week, they have spent time in Orlando, Florida, picketing funerals there. Their message is that God sends violence, that God is responsible for human suffering, that God makes such suffering happen.

Most Christians find this behavior and this theology repulsive. I will take just a minute to explain it. And, because I’m a college professor, I have a PowerPoint slide for you, because, frankly, it’s a bit confusing, and you might get to the end of my explanation and have to look at the whole thing again to understand it.

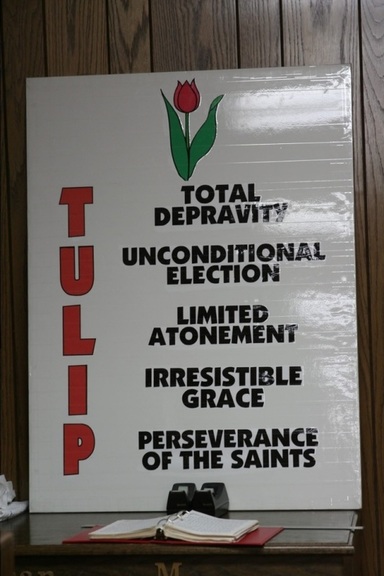

Westboro Baptists are Calvinists, like Presbyterians and some kinds of Baptists and some other common strains of religion. Like other Calvinists, they hold to TULIP, which is a sweet acronym for the contentious theology that explains predestination. The picture shown here stands in the church sanctuary so that people can see it every time they gather.

The “T” is for Total Depravity—that all people are born hopelessly evil, by our very natures, and thus we can do nothing to close the chasm between us and God. Now, other Christians, including non-Calvinists, may believe this, too.

The “U” is for Unconditional Election—the idea that God saves not because of our merit, not because we deserve it. Because we are totally depraved, we can do nothing to make God love us. Again, this is not unique in Christianity.

The “L,” though, is where Calvinists start to distinguish themselves. It stands for Limited Atonement, which means that the salvific death of Christ was limited in its scope. In other words, Jesus’ death was not for all of humanity but only for some. For whom, then? For those God selected—or elected—at the start of time. In other words, before we were born, God decided if Jesus’ death was for us or not. Remember that, because we are all depraved, none of us deserve it. And those who receive it do so without any consideration of their merit—that is, unconditionally.

The “I” is for Irresistible Grace, which means that if God elected you, you can’t say no. If Jesus died for you, then you will be saved. And that will be reflected in your life of obedience.

The “P” is for Perseverance of the Saints, which just means that if you are one of the elect, not only will God have you—he will keep you. You won’t lose your salvation. You never earned it in the first place, and you can’t lose it.

Now, Westboro Baptists are not just Calvinists but Hyper-Calvinists, which is a word that can be used pejoratively, though I do not mean any negative connotation. I mean that they add two doctrines to TULIP: double predestination and absolute predestination. “Double predestination” means that God doesn’t just choose who is going to heaven—God also actively choses, at the start of time, and without any consideration of our merit who goes to hell. A Westboro Baptist once explained it to me this way: We are all on death row. Every single human is a sinner and deserving of death and eternity in hell to follow. If the governor calls and pardons the death row inmate in the cell next to me, I cannot complain. Both of us deserve death; if he is excused from it, not because of his merit, but because of the grace of the governor, I cannot complain. In fact, I can only praise the governor for having mercy at all.

And by “Absolute Predestination,” I mean that God preordains not just salvation, not just who is going to heaven and who is going to hell, but everything. If you hit a red light on the way to church, God made that happen. If you got a mosquito bite this morning, God made that happen. Everything is not just under God’s control but an expression of God’s will.

Because of these beliefs, Westboro Baptists cannot ever know who it is who God loves and who is bound for heaven. Remember: good behavior doesn’t get you into heaven, so we can’t assume that just because someone is behaving well (that is, as defined by the church), that they are heaven-bound. Life-long members of Westboro Baptist Church could be damned! But by this theology, Westboro Baptists can know who is definitely going to hell: the disobedient. In other words, being obedient doesn’t get you into heaven, but being disobedient is a sign that God hates you and damned you before you were born.

So who are the ones Westboro Baptists know are damned? Well, all non-believers. All non-Christians. All non-Westboro Baptists. Americans broadly, but not just us. The whole world. In fact, you can visit their website God Hates the World to find an interactive map. Click on any country, and the church will tell you why God hates it. God hates coal miners, like those killed in the West Sago Mine explosion. God hates astronauts, like those killed in the Columbia explosion. God hates Justin Bieber, Vince Gill, Lady Gaga, women with breast cancer, police officers, the entire US military, and all Christians who all also think gay people go to hell but don’t say so at their funerals, including Jerry Falwell, Franklin Graham, and Pat Robertson.

I have spent a number of years now studying Westboro Baptist Church. It’s a small—larger than Stahl Mennonite, but not by much—congregation from Topeka, Kansas. It’s an independent Baptist church, not associated with any denomination, though they call themselves Primitive Baptists, theologically speaking, though other Primitive Baptists say that they aren’t. How many folks here have heard of them? And has anyone seen them in person?

Well, this church is most famous for its picketing at funerals. Since the early 1990s, they have shown up at funerals, as well as many, many other events, including high school graduations, concerts, public lectures, and other events, to preach their message. For the first 15 years or so, that message focused on their claim that God hates people who are not heterosexual. In the mid-2000s, as American casualties from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan started climbing, they turned their attention to God’s hatred of all of America, as evidenced by soldiers killed in combat. It was that claim that landed them before the Supreme Court in 2010. They picketed the funeral of a Marine from York, Pennsylvania, and though they did not break the law in doing so, the father of the fallen Marine sued them. He won, then he lost the appeal, and he lost before the Supreme Court. So they continue to picket.

This week, they have spent time in Orlando, Florida, picketing funerals there. Their message is that God sends violence, that God is responsible for human suffering, that God makes such suffering happen.

Most Christians find this behavior and this theology repulsive. I will take just a minute to explain it. And, because I’m a college professor, I have a PowerPoint slide for you, because, frankly, it’s a bit confusing, and you might get to the end of my explanation and have to look at the whole thing again to understand it.

Westboro Baptists are Calvinists, like Presbyterians and some kinds of Baptists and some other common strains of religion. Like other Calvinists, they hold to TULIP, which is a sweet acronym for the contentious theology that explains predestination. The picture shown here stands in the church sanctuary so that people can see it every time they gather.

The “T” is for Total Depravity—that all people are born hopelessly evil, by our very natures, and thus we can do nothing to close the chasm between us and God. Now, other Christians, including non-Calvinists, may believe this, too.

The “U” is for Unconditional Election—the idea that God saves not because of our merit, not because we deserve it. Because we are totally depraved, we can do nothing to make God love us. Again, this is not unique in Christianity.

The “L,” though, is where Calvinists start to distinguish themselves. It stands for Limited Atonement, which means that the salvific death of Christ was limited in its scope. In other words, Jesus’ death was not for all of humanity but only for some. For whom, then? For those God selected—or elected—at the start of time. In other words, before we were born, God decided if Jesus’ death was for us or not. Remember that, because we are all depraved, none of us deserve it. And those who receive it do so without any consideration of their merit—that is, unconditionally.

The “I” is for Irresistible Grace, which means that if God elected you, you can’t say no. If Jesus died for you, then you will be saved. And that will be reflected in your life of obedience.

The “P” is for Perseverance of the Saints, which just means that if you are one of the elect, not only will God have you—he will keep you. You won’t lose your salvation. You never earned it in the first place, and you can’t lose it.

Now, Westboro Baptists are not just Calvinists but Hyper-Calvinists, which is a word that can be used pejoratively, though I do not mean any negative connotation. I mean that they add two doctrines to TULIP: double predestination and absolute predestination. “Double predestination” means that God doesn’t just choose who is going to heaven—God also actively choses, at the start of time, and without any consideration of our merit who goes to hell. A Westboro Baptist once explained it to me this way: We are all on death row. Every single human is a sinner and deserving of death and eternity in hell to follow. If the governor calls and pardons the death row inmate in the cell next to me, I cannot complain. Both of us deserve death; if he is excused from it, not because of his merit, but because of the grace of the governor, I cannot complain. In fact, I can only praise the governor for having mercy at all.

And by “Absolute Predestination,” I mean that God preordains not just salvation, not just who is going to heaven and who is going to hell, but everything. If you hit a red light on the way to church, God made that happen. If you got a mosquito bite this morning, God made that happen. Everything is not just under God’s control but an expression of God’s will.

Because of these beliefs, Westboro Baptists cannot ever know who it is who God loves and who is bound for heaven. Remember: good behavior doesn’t get you into heaven, so we can’t assume that just because someone is behaving well (that is, as defined by the church), that they are heaven-bound. Life-long members of Westboro Baptist Church could be damned! But by this theology, Westboro Baptists can know who is definitely going to hell: the disobedient. In other words, being obedient doesn’t get you into heaven, but being disobedient is a sign that God hates you and damned you before you were born.

So who are the ones Westboro Baptists know are damned? Well, all non-believers. All non-Christians. All non-Westboro Baptists. Americans broadly, but not just us. The whole world. In fact, you can visit their website God Hates the World to find an interactive map. Click on any country, and the church will tell you why God hates it. God hates coal miners, like those killed in the West Sago Mine explosion. God hates astronauts, like those killed in the Columbia explosion. God hates Justin Bieber, Vince Gill, Lady Gaga, women with breast cancer, police officers, the entire US military, and all Christians who all also think gay people go to hell but don’t say so at their funerals, including Jerry Falwell, Franklin Graham, and Pat Robertson.

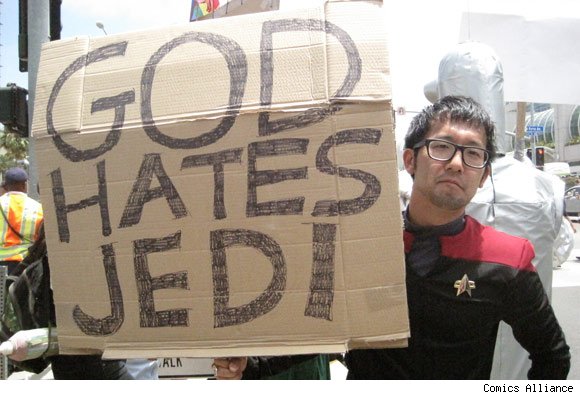

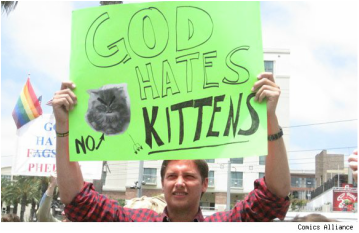

The list of what they think God hates is so extensive that it is actually hard to make fun of because anything seems like it could possibly fit. The image shown here is from a Comic Con convention, where fans of science fiction and fantasy and comic books and such gather to share their interests. Westboro Baptist Church picketed a Comic Con, and this counterprotestor, using humor to address the situation, came out wearing his Star Trek uniform and holding a sign that says “God Hates Jedi.” The joke, of course, is that there is some tension between Trekkies and fans of Star Wars. In the other image, a man holds a sign that says “God Hates Kittens”. Its ridiculousness points to the ridiculousness of Westboro’s signs. And, after you read enough of the signs, you might think that there is some way that a person could conclude that God does, in fact, hate kittens.

One former member recalls holding a sign that says “Gods hates bikinis,” which helped her see the level of control the church sought over its members (who were forbidden from wearing bikinis). God hates bikinis? What about tankinis? What about one piece swimwear that shows a lot of cleavage? And how do we know this? How does God feel about panty hose that twists? Spanx? Itchy elastic? Does God hate the seam in socks as much as my daughter does? Is the person who invented double knit polyester burning in hell right now? Can I stone my neighbor for mowing his grass while wearing shorts, socks, and sandals but no shirt?

Well, I am teasing a bit. Westboro Baptist Church would say that there is logic behind their signs, that there are reasons for every prohibition. Mennonites are familiar with these prohibitions. Indeed, my daughter heads off to a Mennonite camp this week, where two-piece swimwear is prohibited. I don’t necessarily disagree, though I can’t imagine this rousing God’s hatred. Here perhaps I assume that God is too much like me and figures that he’ll choose his battles and not fuss about children’s clothing unless it’s really important, like wearing clothes in public and shoes at the grocery store. But that’s me—the virgin who is careless with her oil. In the parable, the groom seems a lot more likely to hold a grudge.

One former member recalls holding a sign that says “Gods hates bikinis,” which helped her see the level of control the church sought over its members (who were forbidden from wearing bikinis). God hates bikinis? What about tankinis? What about one piece swimwear that shows a lot of cleavage? And how do we know this? How does God feel about panty hose that twists? Spanx? Itchy elastic? Does God hate the seam in socks as much as my daughter does? Is the person who invented double knit polyester burning in hell right now? Can I stone my neighbor for mowing his grass while wearing shorts, socks, and sandals but no shirt?

Well, I am teasing a bit. Westboro Baptist Church would say that there is logic behind their signs, that there are reasons for every prohibition. Mennonites are familiar with these prohibitions. Indeed, my daughter heads off to a Mennonite camp this week, where two-piece swimwear is prohibited. I don’t necessarily disagree, though I can’t imagine this rousing God’s hatred. Here perhaps I assume that God is too much like me and figures that he’ll choose his battles and not fuss about children’s clothing unless it’s really important, like wearing clothes in public and shoes at the grocery store. But that’s me—the virgin who is careless with her oil. In the parable, the groom seems a lot more likely to hold a grudge.

Back to those virgins, the ones who got kicked out. Many Christians have read that story as being about preparation for Jesus’ return. Those who aren’t ready are out, damned, headed to hell. There have been some good refutations of that vision of salvation, including the Rob Bell’s Love Wins: A Book About Heaven, Hell, and the Fate of Every Person Who Ever Lived. For an even better read about hell, though, I have to recommend You’re Not Going to Heaven (and Why It Doesn’t Matter) by Wes Bergen, who was just installed as a pastor at Morgantown Church of the Brethren, just down the road from you all and, like Stahl, in the Allegheny Conference. I will not say much about their views on heaven, which are worth reading—especially Wes’—but I will say that there is some scholarly dispute about whether Jesus actually told this parable or whether it was added by first century Christians who were a bit obsessed with Jesus’ return.

What does Westboro Baptist Church have to do with those foolish virgins? It is this: Westboro Baptist Church spends a lot of time sorting people into wise and foolish virgins, figuring out who might be in and who is out, who God hates and who might God love. I’ll agree, in my worst moments, that this is a fun hobby, especially if I’ve had a bad day at work or am grocery shopping at 5 pm when every other person who forgot to set out dinner hits the store. Thankfully, though, I’m not God, because my list of “foolish virgins” would include students who ask questions that are clearly answered in the syllabus, people who talk on their cell phones in public, and those who chew ice. I assume that the saving grace of Jesus is powerful enough to save ice chewers, but I hope they live in a separate section of heaven from me so I don’t have to hear them.

If that seems petty, it’s precisely illustrates why people have no business figuring out who is in and who is out. It’s hard not to let our personal prejudices creep in. But even when we think we have a clear standard—“what the Bible says”—I argue that we don’t. In this story, the only sin that the foolish virgins committed was not having oil ready. Yes, this was a big deal, but, geez, was it enough of a big deal not to be able to enter the banquet. After all, we don’t know what they did the day of the wedding. Maybe they were so busy doing other bridal attendant tasks that they just forgot or ran out of time. Sure, we condemn them for not having oil, but maybe they were out getting extra ice, or they realized that there wasn’t enough handicapped accessible parking at the party and so were valet parking cars for elderly relatives. Maybe one of them was the mother of the flower girl and had to spend the whole day at the beauty parlor, watching the hair dresser fix the home-made haircut her toddler decided to give herself just that very morning. Point is, we don’t know, and before we join in condemning women for failing to get everything on their to-do list done, we could take a moment to remember all the times we forgot the oil for the lamp, the overdue school lunch money, the donuts for the morning meeting, the anniversary gift, the permission slip for the child’s field trip, maybe even the actual child, who we forgot at daycare.

This parable suggests, in the reading I’m giving it here, which is actually a pretty typical reading in the kinds of conservative churches I research, including those far more polite than Westboro Baptist Church, that we can get kicked out of God’s kingdom, out of relationship with other Christians, out of the kingdom of God, and out of heaven, for an offense as simple as forgetting the oil. What I don’t like about that is that it seems so unpredictable; the bridegroom seems so spiteful, so fickle, his approval and welcome so precarious. What kind of bridezilla won’t seat a late guest? I know, it’s rude to be late. I know it’s rude to be late. I know, I know, I know. (Ask me how I know. Because I have heard the lecture numerous times over my life.) But I don’t see how it’s a relationship breaker.

And so I get a vision of God, from this reading, that is spiteful and picky about things I can’t anticipate. Someone who condemns me for not having oil might also condemn me for a million other things that I don’t see as such a big deal. Eating shellfish, wearing mixed fiber clothing, planting two different seeds in the same hole in the ground. You can’t get ahead of this God because you can’t know what the rules are because there are so many of them and because they aren’t grounded in anything useful. Maybe God does hate Jedi and kittens. Maybe God does slam the door in the face of those who don’t have their spiritual house in order. Maybe God wants us to slam the door in the face of those who don’t fit what we think the Bible says, too. Maybe this passage is our permission slip to kick out those who are not meeting our expectations. Maybe that includes some of the same people Westboro Baptist Church says God hates.

Because these are presumably the words of Jesus, I can’t ignore them. I also can’t square them with the others parables of Jesus, who tells us that the shepherd finds every lost lamb and the widow searches for every coin, who throws open wide the gates even though the road is narrow and hard. The indomitable Michele Hersbherger, who teaches Bible at Hesston College, teachs her students that “when the Bible seems to disagree, Jesus is the referee.” I love that saying, which reminds us to see through the lens of Christ. But here, it’s exactly Jesus’ parable that is my problem.

So let me approach it again: No matter what those ten virgins had to do, they also had to have oil for the lamps. It was their most important job. Why? Because the oil would allow them to welcome and protect others who were attending the festivities. The oil in the lamps would guide other people to the groom. The oil welcomed people to the party. The light of those lamps said, “You are included. Come here and be part of this banquet. Come and these lights will keep you safe.” In this reading, the mistake that the five foolish virgins made is a grave one. It is one of not welcoming and caring for the guests. If everyone is invited to the kingdom of God, our gravest mistake—the one that will land us on the outside of the banquet hall and have Jesus denying us—is our failure to welcome and protect those who need our welcome and protection.

The last picture I share with you today comes from yesterday’s Miami Herald. It is of people participating in Angel Action, which is a counterprotest against Westboro Baptist Church that was created in response to the church’s picket of Matthew Shepard’s funeral. You might recall that Shepard was a gay college student murdered in Wyoming in the 1990s. His funeral was one of the first high-profile ones that Westboro Baptists picketed. In response, Shepard’s friends sewed these costumes. You use PVC pipes and white sheets to create “wings” that work on a lever system. When you pull down, the wings rise high in the air—8 or 9 feet, easily—and block the signs. Westboro Baptist Church is still able to exercise its right to be present, but these Angels—in Laramie, Wyoming, in Orlando, Florida—stand between their signs and those trying to come to the banquet, using their protective wings to guide those who want in.

What does Westboro Baptist Church have to do with those foolish virgins? It is this: Westboro Baptist Church spends a lot of time sorting people into wise and foolish virgins, figuring out who might be in and who is out, who God hates and who might God love. I’ll agree, in my worst moments, that this is a fun hobby, especially if I’ve had a bad day at work or am grocery shopping at 5 pm when every other person who forgot to set out dinner hits the store. Thankfully, though, I’m not God, because my list of “foolish virgins” would include students who ask questions that are clearly answered in the syllabus, people who talk on their cell phones in public, and those who chew ice. I assume that the saving grace of Jesus is powerful enough to save ice chewers, but I hope they live in a separate section of heaven from me so I don’t have to hear them.

If that seems petty, it’s precisely illustrates why people have no business figuring out who is in and who is out. It’s hard not to let our personal prejudices creep in. But even when we think we have a clear standard—“what the Bible says”—I argue that we don’t. In this story, the only sin that the foolish virgins committed was not having oil ready. Yes, this was a big deal, but, geez, was it enough of a big deal not to be able to enter the banquet. After all, we don’t know what they did the day of the wedding. Maybe they were so busy doing other bridal attendant tasks that they just forgot or ran out of time. Sure, we condemn them for not having oil, but maybe they were out getting extra ice, or they realized that there wasn’t enough handicapped accessible parking at the party and so were valet parking cars for elderly relatives. Maybe one of them was the mother of the flower girl and had to spend the whole day at the beauty parlor, watching the hair dresser fix the home-made haircut her toddler decided to give herself just that very morning. Point is, we don’t know, and before we join in condemning women for failing to get everything on their to-do list done, we could take a moment to remember all the times we forgot the oil for the lamp, the overdue school lunch money, the donuts for the morning meeting, the anniversary gift, the permission slip for the child’s field trip, maybe even the actual child, who we forgot at daycare.

This parable suggests, in the reading I’m giving it here, which is actually a pretty typical reading in the kinds of conservative churches I research, including those far more polite than Westboro Baptist Church, that we can get kicked out of God’s kingdom, out of relationship with other Christians, out of the kingdom of God, and out of heaven, for an offense as simple as forgetting the oil. What I don’t like about that is that it seems so unpredictable; the bridegroom seems so spiteful, so fickle, his approval and welcome so precarious. What kind of bridezilla won’t seat a late guest? I know, it’s rude to be late. I know it’s rude to be late. I know, I know, I know. (Ask me how I know. Because I have heard the lecture numerous times over my life.) But I don’t see how it’s a relationship breaker.

And so I get a vision of God, from this reading, that is spiteful and picky about things I can’t anticipate. Someone who condemns me for not having oil might also condemn me for a million other things that I don’t see as such a big deal. Eating shellfish, wearing mixed fiber clothing, planting two different seeds in the same hole in the ground. You can’t get ahead of this God because you can’t know what the rules are because there are so many of them and because they aren’t grounded in anything useful. Maybe God does hate Jedi and kittens. Maybe God does slam the door in the face of those who don’t have their spiritual house in order. Maybe God wants us to slam the door in the face of those who don’t fit what we think the Bible says, too. Maybe this passage is our permission slip to kick out those who are not meeting our expectations. Maybe that includes some of the same people Westboro Baptist Church says God hates.

Because these are presumably the words of Jesus, I can’t ignore them. I also can’t square them with the others parables of Jesus, who tells us that the shepherd finds every lost lamb and the widow searches for every coin, who throws open wide the gates even though the road is narrow and hard. The indomitable Michele Hersbherger, who teaches Bible at Hesston College, teachs her students that “when the Bible seems to disagree, Jesus is the referee.” I love that saying, which reminds us to see through the lens of Christ. But here, it’s exactly Jesus’ parable that is my problem.

So let me approach it again: No matter what those ten virgins had to do, they also had to have oil for the lamps. It was their most important job. Why? Because the oil would allow them to welcome and protect others who were attending the festivities. The oil in the lamps would guide other people to the groom. The oil welcomed people to the party. The light of those lamps said, “You are included. Come here and be part of this banquet. Come and these lights will keep you safe.” In this reading, the mistake that the five foolish virgins made is a grave one. It is one of not welcoming and caring for the guests. If everyone is invited to the kingdom of God, our gravest mistake—the one that will land us on the outside of the banquet hall and have Jesus denying us—is our failure to welcome and protect those who need our welcome and protection.

The last picture I share with you today comes from yesterday’s Miami Herald. It is of people participating in Angel Action, which is a counterprotest against Westboro Baptist Church that was created in response to the church’s picket of Matthew Shepard’s funeral. You might recall that Shepard was a gay college student murdered in Wyoming in the 1990s. His funeral was one of the first high-profile ones that Westboro Baptists picketed. In response, Shepard’s friends sewed these costumes. You use PVC pipes and white sheets to create “wings” that work on a lever system. When you pull down, the wings rise high in the air—8 or 9 feet, easily—and block the signs. Westboro Baptist Church is still able to exercise its right to be present, but these Angels—in Laramie, Wyoming, in Orlando, Florida—stand between their signs and those trying to come to the banquet, using their protective wings to guide those who want in.

In the parable, the groom arrives anyway, but the virgins’ foolishness risked his guests. The groom does not need help finding his way. His guests, though, need the protection of a lit path. My hope for Stahl Mennonite is that you will always be a church that keeps your lamps lit, not for the groom, but for his guests.

Rebecca Barrett-Fox is an expert on the Westboro Baptist Church. Her book entitled God Hates is being released this summer by University of Kansas Press.

Rebecca Barrett-Fox is an expert on the Westboro Baptist Church. Her book entitled God Hates is being released this summer by University of Kansas Press.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed